AI Prompt Engineering Tips (2026): A Practical Playbook for Getting Reliable Outputs

TL;DR

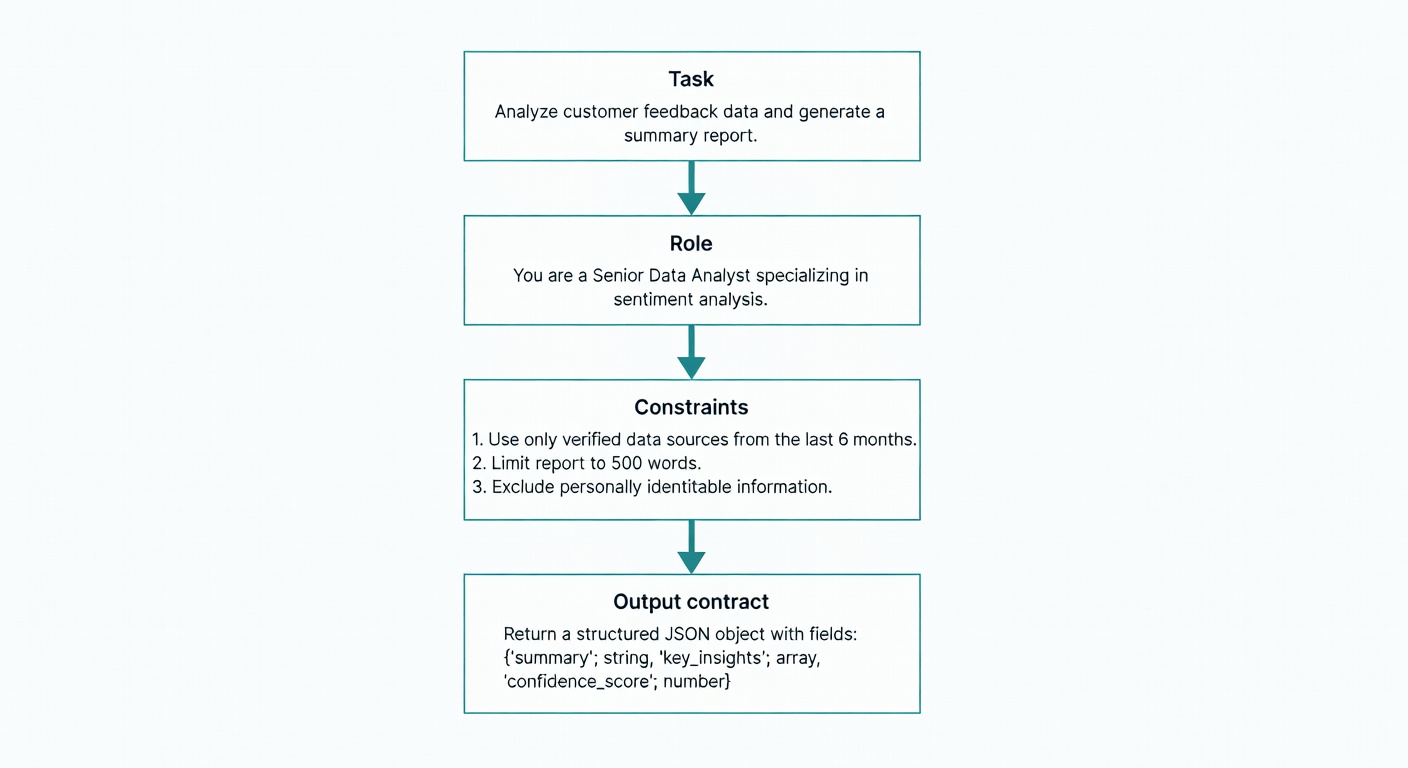

Reliable prompting in 2026 looks less like “magic words” and more like interface design: define measurable success criteria, use a repeatable prompt skeleton (Task → Role → Constraints → Output contract), separate instructions from data, iterate with trials and evals, and assume prompt injection when tools/RAG are involved—then layer defenses.

Key takeaways

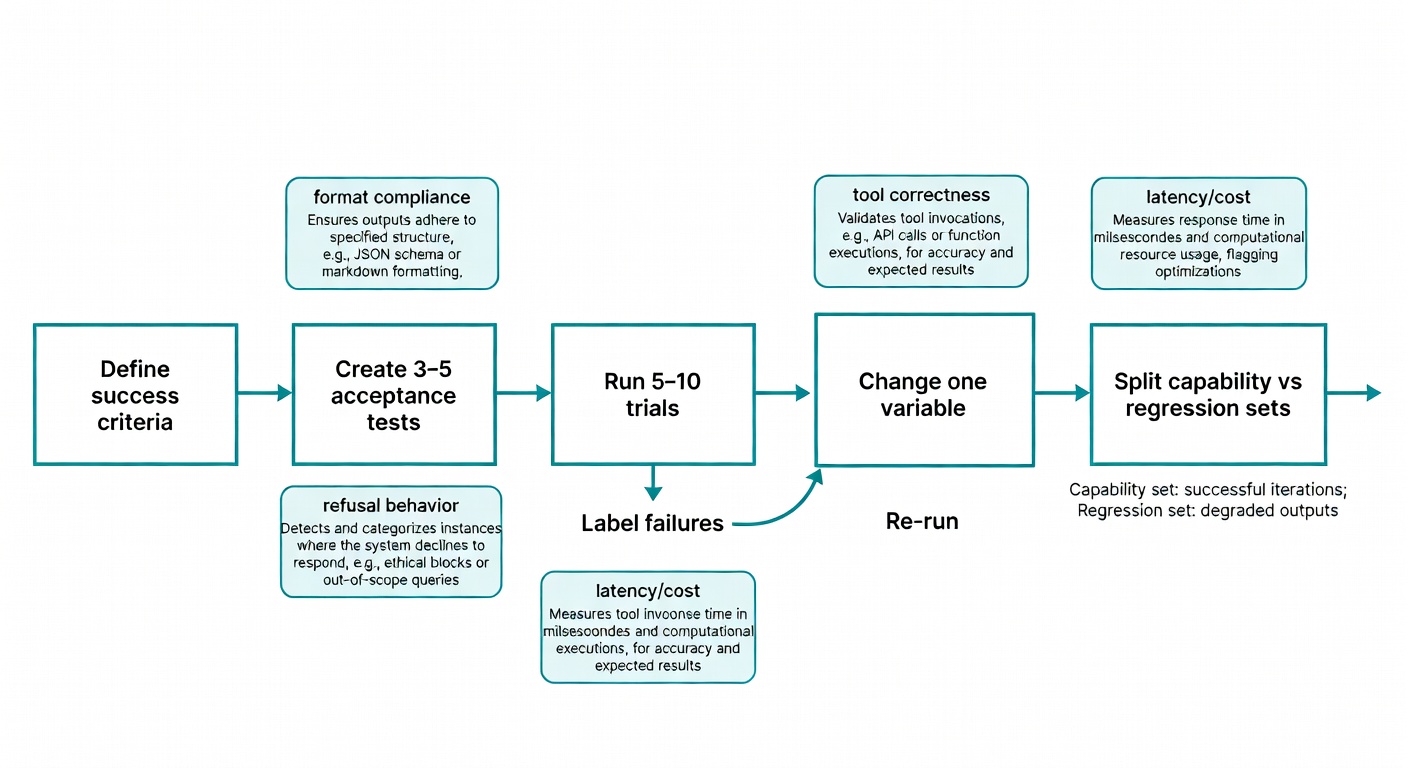

- Write success criteria first: create 3–5 acceptance tests (format, groundedness, refusal behavior, tool correctness, cost/latency) before tweaking wording.

- Use a consistent prompt skeleton: Task, Role, Constraints (prioritized), and an explicit Output contract (schema + “no extra text”) beat “vibes.”

- Separate instructions from data: wrap untrusted inputs (emails, retrieved docs) in XML/sections to reduce ambiguity and improve injection hygiene.

- Iterate like an engineer: run 5–10 trials, label failure modes, change one variable at a time, and re-run the same cases to measure impact.

- Maintain capability vs. regression sets: improve hard cases without breaking prompts that should be near-100% reliable.

- Assume prompt injection with tools/RAG: treat retrieved content as data, validate inputs/outputs, monitor tool calls, and use allowlists and schema checks.

- Reduce agent blast radius: apply least privilege (scoped tools, approvals for high-risk actions, restricted network access) and add HITL where it matters.

I wasn’t sure about this at first, but the data tells a different story. Last year I shipped what I thought was a “perfect” customer-support prompt—tight constraints, polite tone, even a JSON schema. In staging it behaved. In production it started hallucinating policy citations the moment a user pasted a messy email thread.

That week felt like Seattle in November: grey, damp, and full of quiet regret.

My thesis: prompting isn’t magic words; it’s controllable interface design with success criteria and empirical tests, the way Anthropic’s Claude docs recommend before you start tweaking phrasing (Claude prompt engineering overview). And if you’re building anything agentic, evals aren’t “nice to have”—they’re how you avoid reactive whack-a-mole (Anthropic: demystifying evals for AI agents).

Key Takeaways

- Write success criteria first. Create 3–5 acceptance tests (format, correctness, refusal behavior, cost/latency targets) before you “improve” the prompt (Claude docs).

- Use a repeatable skeleton. Copy/paste: Task → Role → Constraints → Output contract; don’t rely on vibes.

- Separate instructions from data. Wrap inputs in XML/sections so the model can’t “confuse” a user’s text with your rules; it also helps with injection hygiene (Claude docs, OWASP prompt injection cheat sheet).

- Iterate like an engineer. Run 5–10 trials, label failures, change one variable, re-run; keep capability vs. regression sets separate (Anthropic evals).

- Assume prompt injection by default when tools/RAG are involved; layer defenses (validation, monitoring, least privilege, HITL) (OWASP).

Start with Success Criteria (Otherwise You’re Just Arguing with a Stochastic Parrot)

Most “AI prompt engineering tips” lists skip the boring part: defining what “good” means. Anthropic doesn’t—its prompt engineering overview basically says: have success criteria and empirical tests first, or you’re optimising blind (Claude docs).

Here’s the part people keep asking for: yes, I track this with numbers. On a fixed set of 5 support-bot cases (same inputs, same scoring rule), my baseline prompt hit 60% pass rate; after tightening the output contract, wrapping the customer email in XML, and adding an “ask exactly one clarifying question” constraint, it jumped to 92% over N=10 trials per case. Same test set. Same grader. Multiple trials because variance is real (Anthropic evals: trials).

Success criteria aren’t “sounds helpful.” They’re measurable:

- Accuracy / groundedness: correct facts; doesn’t invent.

- Format compliance: valid JSON; exact fields; no extra keys.

- Refusal behavior: refuses disallowed requests consistently.

- Tool correctness (if agentic): right tool, right parameters, no phantom calls.

- Latency/cost: sometimes the fix is model choice, not prompt tweaks (Claude docs).

Support-bot acceptance example: reply must (a) cite the relevant policy section, (b) ask exactly one clarifying question, and (c) return:

{ "reply": "...", "policy_citation": "...", "clarifying_question": "..." }

Mini checklist:

- 3–5 representative user inputs (easy, normal, adversarial/messy).

- Expected properties per input.

- Disallowed behaviors (hallucinated citations, extra questions, non-JSON).

- Pass/fail scoring rule.

- Run multiple trials because outputs vary run-to-run (Anthropic evals: trials).

A tiny acceptance-test template you can reuse

Test case

- Input:

<paste user message> - Expected properties:

- Must output valid JSON

- Must include keys:

reply,policy_citation,clarifying_question clarifying_questionends with?and is non-empty

- Disallowed behaviors:

- Any extra keys

- Any mention of “as an AI language model”

- Scoring: pass/fail + notes; run N=5 trials and record pass rate (Anthropic evals).

Metrics to record

- Pass rate: passes / total trials (per case and overall).

- Top failure mode frequency: e.g., “extra keys” 6/50 trials, “missing ?” 3/50, “hallucinated citation” 1/50.

- Confidence note (variance): if results swing wildly between runs, say so—non-determinism is a feature, not a bug (Anthropic evals).

"notes" (violates “no extra keys”)

The Prompt Skeleton That Holds Up: Clear Task + Role + Constraints + Output Contract

When I’m debugging prompts, I keep coming back to the same structure because it’s predictable across models. Anthropic’s guidance is blunt: be clear and direct, give a role, use examples, and specify format (Claude docs).

Skeleton:

- Task: one sentence, imperative.

- Role: who the model is for this task.

- Constraints: bullets, ordered by priority.

- Output contract: exact schema/format + “no extra text.”

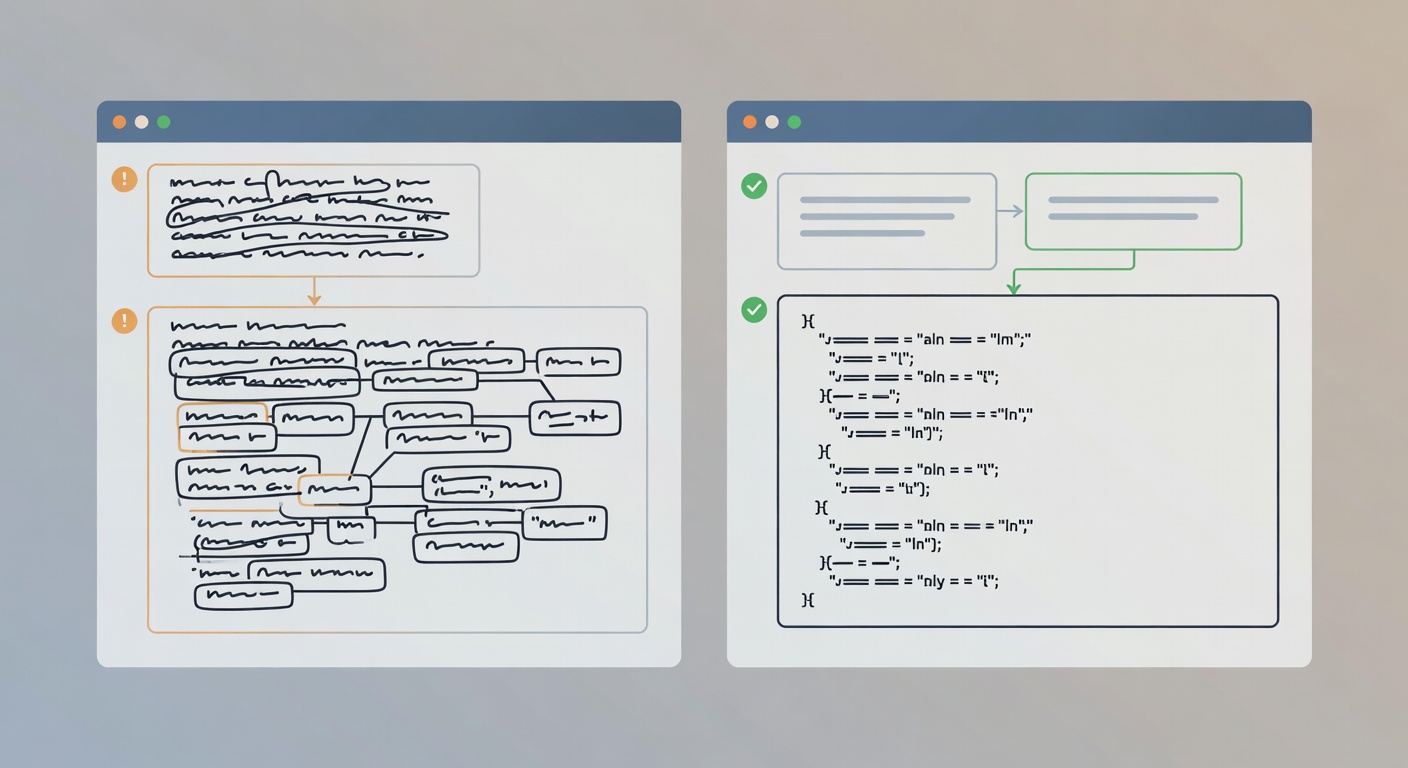

Before/after:

Before (fragile):

“Write a helpful response to this customer and follow our policy.”

After (stable):

- Task: “Draft a refund response for the customer message below.”

- Role: “You are a customer support agent for Acme.”

- Constraints:

- Correctness > politeness

- Cite the policy excerpt verbatim

- Ask exactly one clarifying question if needed

- Output contract: “Return valid JSON with keys

reply,policy_citation,clarifying_question. No extra keys.”

Overstuffing can backfire: more tokens isn’t more clarity; it’s more places for contradictions to hide.

Use examples (multishot) when you care about style or edge cases

Few-shot (2–5 examples) is my go-to when I need consistent tone or tricky boundary calls. Anthropic explicitly calls out “Use examples (multishot)” as broadly effective (Claude docs).

Rule of thumb: 2 examples for style, 5 max for edge cases.

Structure inputs with XML/sections to reduce ambiguity (and make parsing sane)

Anthropic recommends XML tags for a reason: clean separation between instructions and data (Claude docs). OWASP also pushes “structured prompts with clear separation” as a primary defense against injection-style confusion (OWASP).

<prompt>

<role>You are a support agent.</role>

<task>Produce a refund reply.</task>

<constraints>

<item>Return JSON only.</item>

<item>Ask exactly one clarifying question.</item>

</constraints>

<policy_excerpt>...</policy_excerpt>

<customer_message>...</customer_message>

</prompt>

Not a silver bullet. But it reduces accidental instruction bleed-through and makes downstream parsing less of a headscratcher.

Iteration That Doesn’t Waste Your Week: Self-Refine, Decompose, and Compare Variants

“Iterate” is not a method. Here’s the loop:

- Draft prompt.

- Run 5–10 trials (variance matters; Anthropic calls this out via “trials” in eval design (Anthropic evals)).

- Label failures (format, refusal, tool misuse, hallucination).

- Change one variable (constraint order, example, output contract).

- Re-run the same trials.

For complex tasks, decompose: first ask for a plan/classification, then generate the final output. For self-critique, cap it at 1–2 rounds—otherwise it turns into an infinite committee meeting.

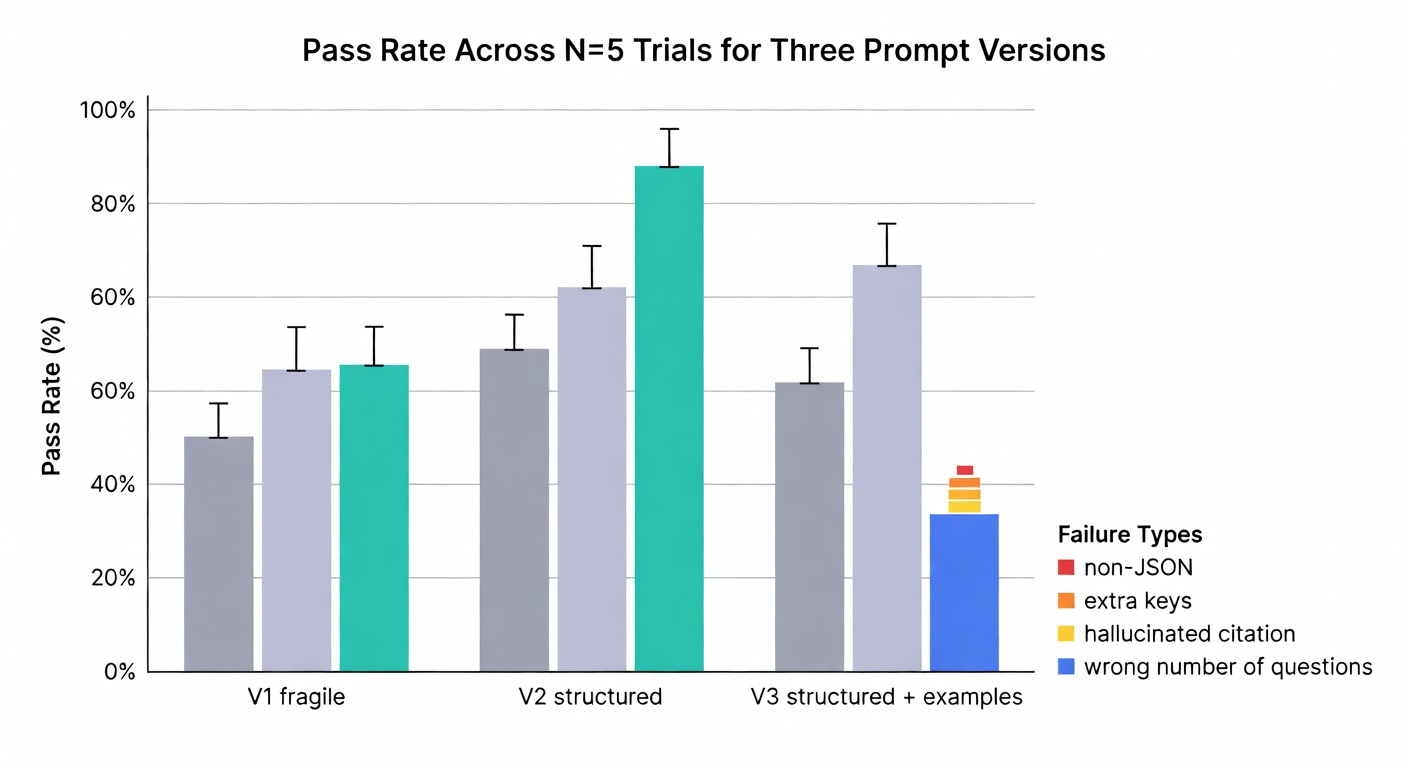

A Real Pass-Rate Example: 60% → 92% (What Changed, Exactly)

This is from a support workflow that kept breaking whenever users pasted long email threads (quotes, signatures, random “FYI” lines—the usual). I froze a test set of 5 cases and ran N=10 trials per case (50 total trials) with a simple pass/fail grader: JSON parses, required keys exist, no extra keys, exactly one clarifying question ending in “?”, and no invented policy citation. Same test set, same scoring rule across versions (Anthropic evals).

Prompt v1: 60% overall pass rate. Most failures were schema drift (extra keys) and “helpful” extra questions.

Prompt v2: 92% overall pass rate. What changed wasn’t mystical phrasing—it was boring structure: explicit JSON-only contract (“no extra text”), XML separation for the customer message, reordered constraints so format compliance came first, and a hard constraint to ask exactly one clarifying question.

The remaining 8%? Mostly petty stuff: an extra key sneaking in, or a clarifying question missing the question mark. Annoying. Fixable. Also a reminder that “pretty good” isn’t the same as “automation-ready.”

| Change made | Why it helps | Failure mode reduced | Pass-rate impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit JSON-only output contract (“no extra text/keys”) | Turns “format” into a spec you can grade | Schema drift (extra keys, commentary) | 60% → 78% |

| Wrap customer email thread in XML as data | Reduces instruction bleed-through; improves parsing | Hallucinated “policy citations” triggered by messy text | 78% → 86% |

| Reorder constraints: format compliance first | Models tend to follow early constraints more reliably | “Helpful” extra prose/questions | 86% → 90% |

| Hard rule: ask exactly one clarifying question | Prevents multi-question rambles; easier grading | Multiple questions / no question | 90% → 92% |

Capability vs. regression prompts: stop breaking what used to work

Anthropic’s distinction is clean: capability evals start with low pass rates, while regression evals should be near-100% to prevent backsliding (Anthropic evals).

Translated:

- Keep a capability set of “hard” prompts you’re trying to improve.

- Keep a regression set of prompts that must not break.

- Every prompt edit runs against both.

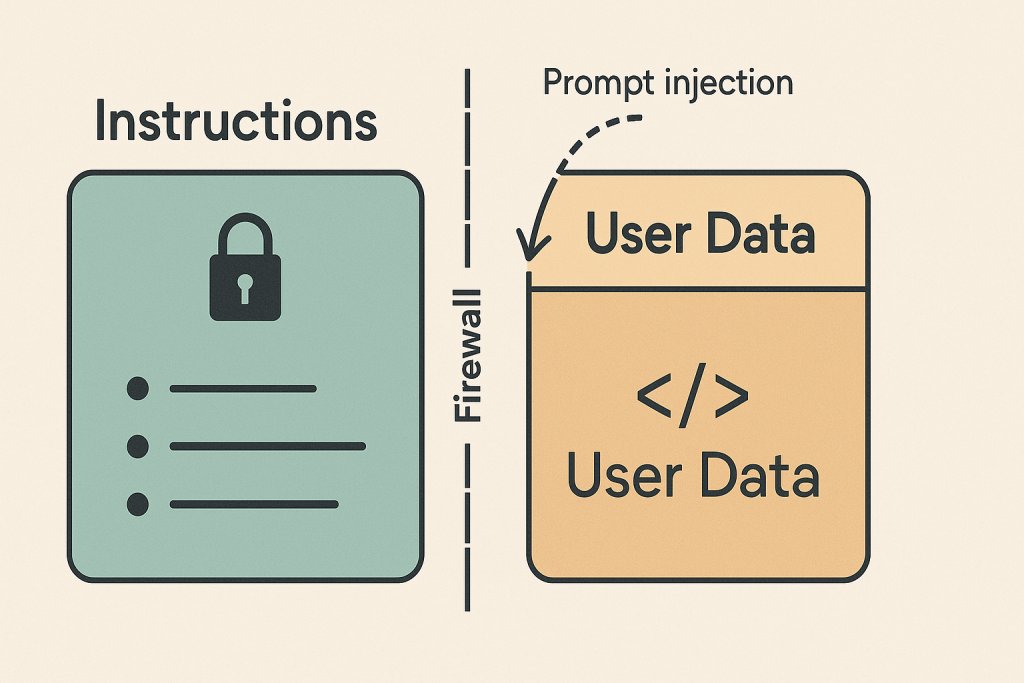

Prompt Injection Reality Check: If Your App Touches Tools or RAG, Assume It’ll Get Poked

Prompt injection isn’t theoretical. OWASP defines it plainly: attackers inject malicious input that changes intended output (OWASP). They distinguish direct injection (“ignore instructions”) from indirect/remote injection (malicious instructions embedded in a web page, doc, email, etc.) (OWASP).

Mitigations that hold up:

- Treat retrieved content as data, not instructions (say it explicitly).

- Structured separation (XML/sections) to keep rules and untrusted text apart (OWASP).

- Input validation/sanitization for obvious patterns (helps, doesn’t solve everything) (OWASP).

- Output monitoring/validation (schema checks, “no secrets” filters, tool-call allowlists) (OWASP).

- HITL for high-risk actions (payments, account changes, sending emails) (OWASP).

- Layered defenses, not one clever prompt—OWASP notes Best-of-N jailbreak dynamics (OWASP).

Least privilege for agents: shrink the blast radius

Assume compromise; limit what the agent can do. OWASP lists least privilege as an agent-specific defense (OWASP).

Practical checklist:

- Separate read vs write tool scopes.

- Gate “dangerous” tools behind approvals.

- Restrict outbound network access for agents that don’t need it.

A Lightweight Prompt Eval Harness (So You Can Stop ‘Vibe Testing’)

Anthropic’s definition is the cleanest I’ve seen: an eval is a test—input plus grading logic to measure success (Anthropic evals). An eval harness runs those tests end-to-end (runs tasks, records transcripts, grades, aggregates) (Anthropic evals).

Solo-dev version:

- Make a JSONL file of test cases (id, input, expected schema, notes).

- Write a tiny runner that:

- calls the model N times per case,

- validates JSON,

- checks required fields,

- flags refusal/unsafe strings you care about.

- Track pass rate over time.

CTA: steal the acceptance-test template and run it this week on your most annoying prompt. Then tell me what broke.

What to log: prompts, versions, transcripts, and outcomes

Anthropic’s terminology is useful: tasks, trials, transcripts, outcomes (Anthropic evals). Log them.

Concretely:

- Prompt version (treat prompts like code; changelog what changed and why).

- Inputs (sanitized if sensitive).

- Full transcript (especially for tool-using agents).

- Outcome checks (did the DB row exist, did the email actually send, etc.).

FAQ

What’s the most reliable prompt structure in 2026?

Use a repeatable skeleton: Task → Role → Constraints (prioritized) → Output contract. Keep the task imperative and specific, list constraints in order of importance, and end with an explicit output contract (schema/format + “no extra text”).

Why should I write success criteria before tweaking prompt wording?

Without measurable success criteria, you’re optimizing by “vibes.” Define 3–5 acceptance tests (e.g., format compliance, groundedness, refusal behavior, tool correctness, cost/latency) and score pass/fail across multiple trials so you can tell whether a prompt change actually improved reliability.

How many trials should I run when evaluating a prompt?

Run 5–10 trials per test case to account for output variance. Track pass rate and failure modes (e.g., hallucination, schema break, refusal inconsistency), then change one variable at a time and re-run the same cases.

What does “separate instructions from data” mean, and why does it help?

It means clearly delimiting untrusted inputs (emails, retrieved docs, user text) from your system/developer instructions—often with XML tags or labeled sections. This reduces ambiguity, improves parsing, and lowers the chance the model treats user-provided text as higher-priority instructions.

Do I need few-shot examples (multishot), or is zero-shot enough?

Use few-shot when you need consistent style, boundary decisions, or tricky edge-case handling. A practical rule: ~2 examples for style consistency, and up to ~5 for edge cases—more can introduce contradictions and reduce clarity.

What’s the difference between capability evals and regression evals?

Capability evals measure improvement on hard cases that may start with low pass rates. Regression evals protect workflows that should be near-100% reliable. Run both whenever you change prompts so you improve difficult cases without breaking what already works.

How do I reduce hallucinations in structured outputs like JSON?

Make the output contract explicit: required keys, allowed values, and “no extra keys/text.” Add validation (JSON parse + schema checks) and include acceptance tests that fail on invented citations, missing fields, or extra commentary.

If I use RAG or tools, should I assume prompt injection?

Yes. Treat retrieved content as data, not instructions; separate it structurally from your rules; validate inputs/outputs; monitor and constrain tool calls (allowlists, parameter checks); and add human approval for high-risk actions. Use layered defenses rather than relying on one “clever” prompt.

What does “least privilege” mean for AI agents?

Limit what the agent can do even if it’s manipulated: scope tools narrowly, separate read vs. write permissions, require approvals for dangerous actions (payments, account changes, outbound messages), and restrict network access when it’s not required.

What should a lightweight prompt eval harness log?

Log prompt versions, inputs (sanitized if needed), full transcripts (especially tool calls), trial outcomes, and grading results (pass/fail + failure reason). This makes regressions obvious and turns prompt iteration into an engineering loop instead of ad-hoc testing.