AI Detection Tools Accuracy: What They Get Right, Where They Break, and How to Use Them Without Wrecking Trust

I’ve debugged models that looked confident and were still wrong. Same vibe here: “AI detection tools accuracy” sounds crisp, but in practice it’s a probability score wrapped in authority—and that combo can get people hurt if we treat it like a verdict. MIT’s guidance is blunt that detectors have high error rates and can trigger false accusations; OpenAI even shut down its own detector after accuracy issues (MIT Sloan). The USD law library guide lands in the same place: don’t use detectors as the sole indicator of misconduct (USD).

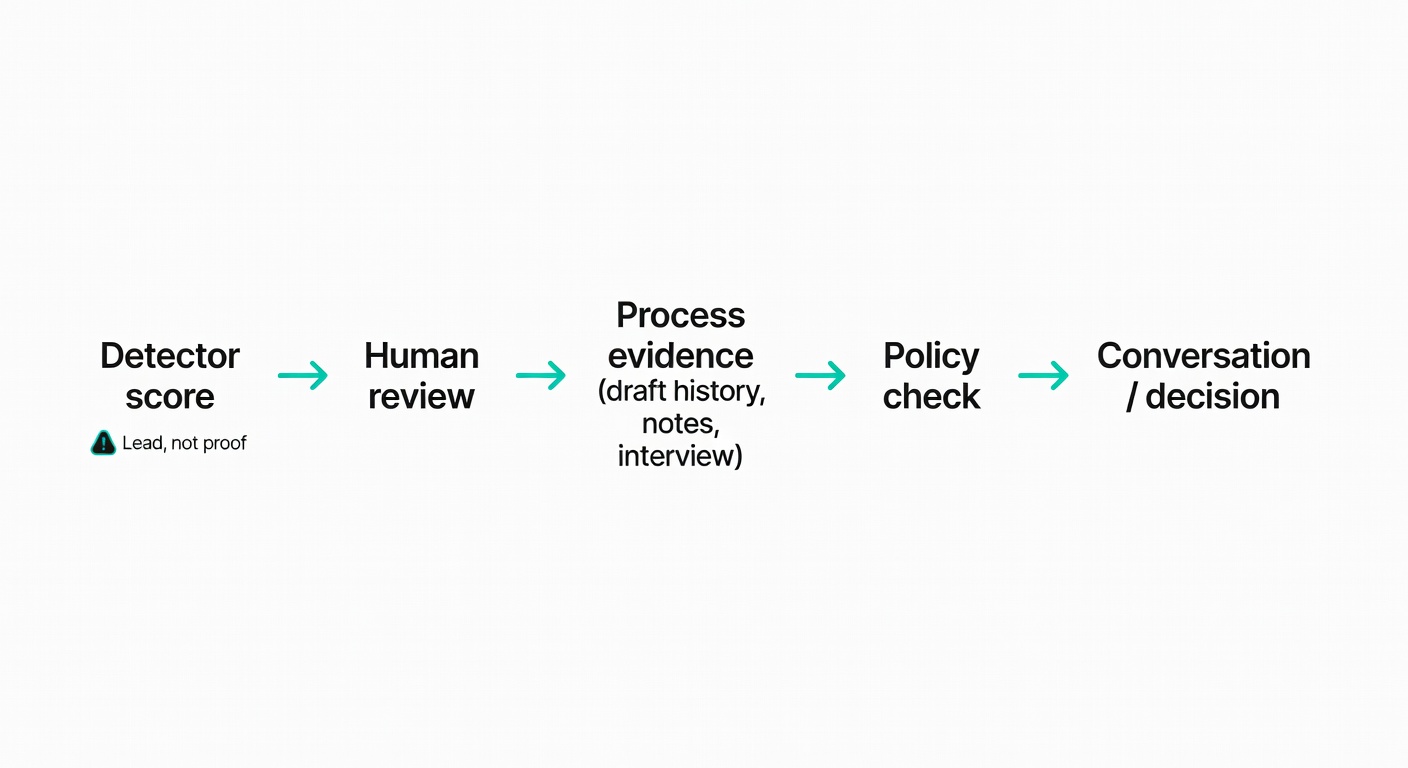

My thesis: treat detector outputs as leads for human review, not proof—especially once you enter the messy world of hybrid writing.

TL;DR

- AI detectors are probabilistic; “accuracy” is incomplete without false positives and false negatives (EdScoop).

- False positives are the fastest way to wreck trust—especially in classrooms and other high-stakes settings (MIT Sloan, USD).

- Hybrid and paraphrased text is where detectors wobble; Temple found Turnitin struggled most on hybrid samples (Temple PDF).

- Use scores as triage, then ask for process evidence (drafts, notes, version history, process statements) (MIT Sloan, KU CTE).

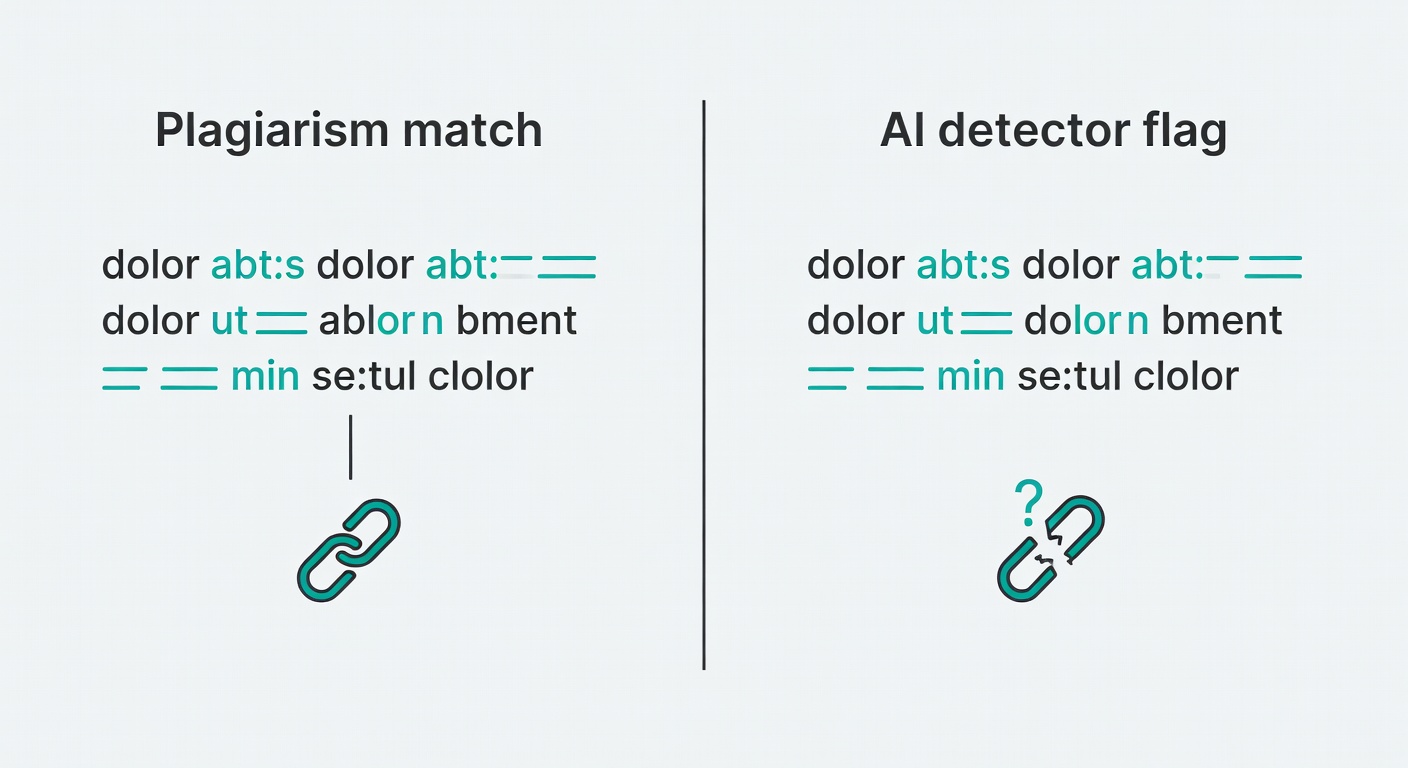

- Don’t treat sentence highlights like plagiarism “receipts”; they’re inference, not link-backed proof (Temple PDF).

- Next step: publish a clear policy, standardize a review workflow, and build an appeal/response path before you rely on any detector (MIT Sloan).

Safe Use Checklist (High-Stakes Settings)

Key Takeaways

“Accuracy” without false-positive and false-negative context is mostly marketing noise—and it’s how you end up with confident-sounding numbers that still produce unfair outcomes (EdScoop). In practice, the hardest case isn’t “pure human” or “pure AI”; it’s hybrid writing and light paraphrasing, where attribution gets fuzzy and detectors drift (Temple PDF).

So treat detector output as a conversation starter, not an indictment—KU’s CTE says exactly that, quoting Turnitin’s own scientist: “take our predictions… with a big grain of salt” and “You, the instructor, have to make the final interpretation” (KU CTE). Pair scores with process evidence and clear policy; MIT explicitly recommends transparency tools like process statements (MIT Sloan).

With that framing in place, let’s get precise about what detector “accuracy” does—and doesn’t—mean.

Pull Quotes

“AI detection software is far from foolproof—in fact, it has high error rates and can lead instructors to falsely accuse students of misconduct.” — MIT Sloan

“that means you’ll have to take our predictions… with a big grain of salt,” and “You, the instructor, have to make the final interpretation.” — David Adamson (quoted by KU CTE)

“These claims of accuracy are not particularly relevant by themselves,” — Chris Callison-Burch (EdScoop)

Temple’s evaluation warns that sentence-level highlighting can mislead in hybrid writing because flagged sections may not correspond to the AI-generated portions (Temple PDF).

What “Accuracy” Actually Means for AI Detectors (and Why It’s Easy to Misread)

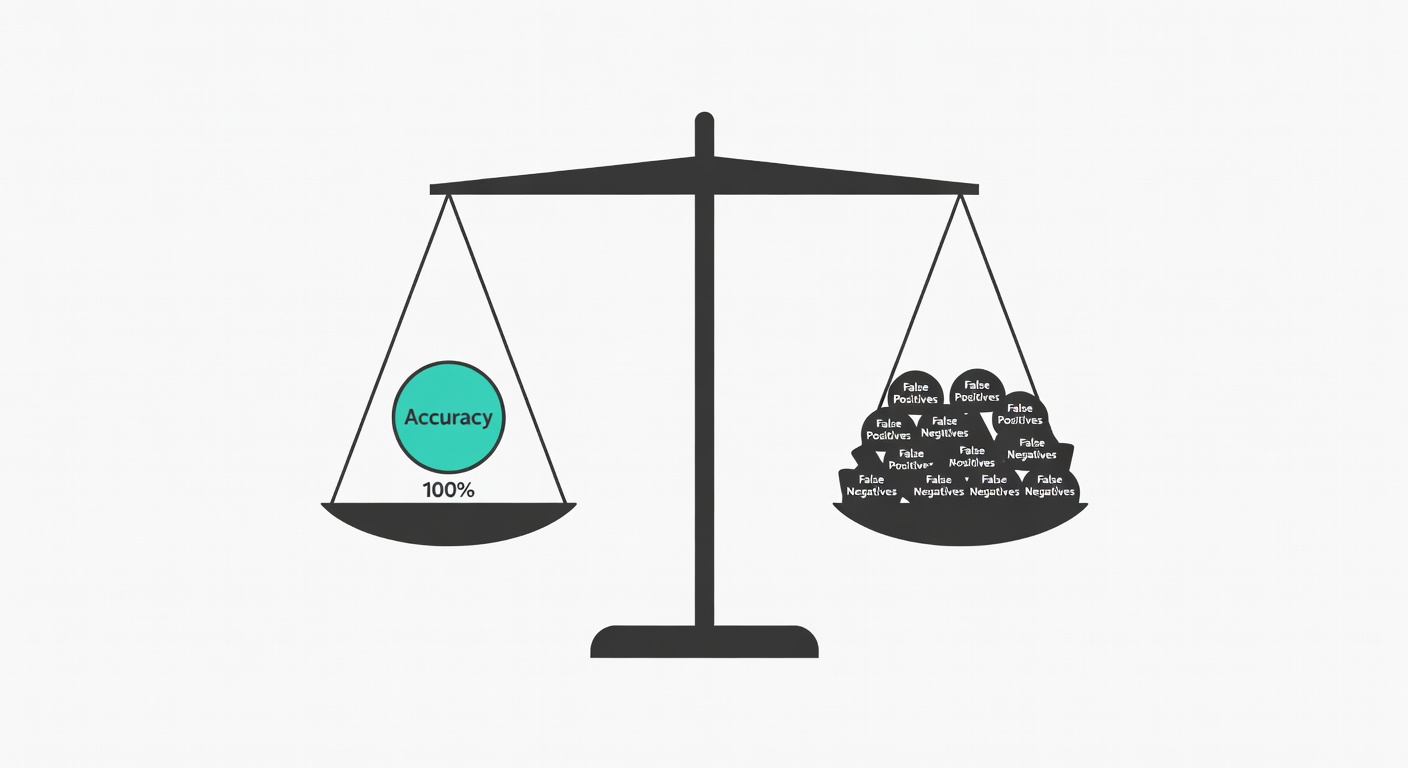

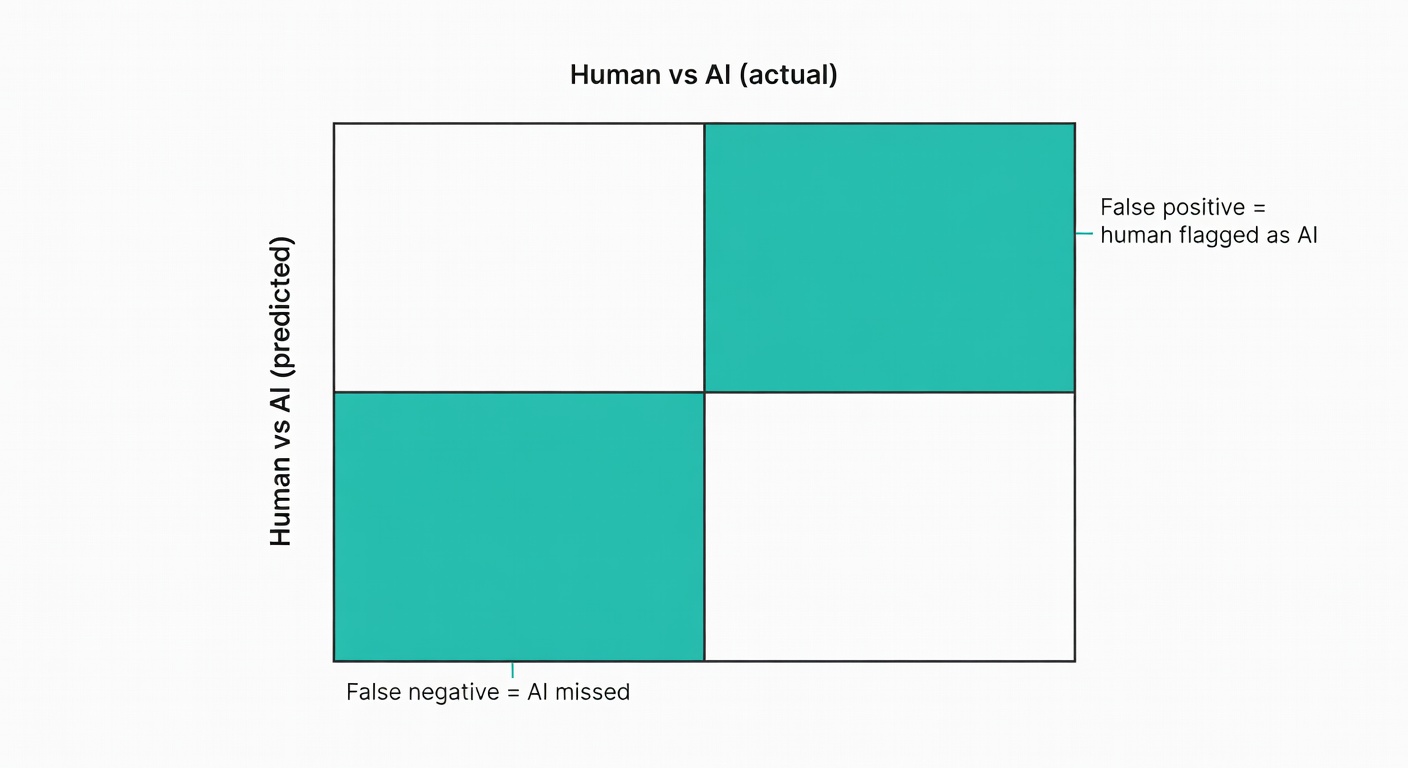

Accuracy is the percent of “right” classifications overall. Useful, but incomplete—because the two outcomes that matter operationally are false positives (wrongly accusing humans) and false negatives (missing AI).

Most detectors are tuned around a trade-off: reduce false positives and you’ll miss more AI. Turnitin says it prioritizes a <1% false positive rate to avoid false accusations (Turnitin), and USD notes Turnitin may miss roughly 15% of AI-generated text in a document (USD). That design choice is defensible; it also means the score is a lead, not a verdict.

Base rates are the quiet gotcha: if most submissions are human-written, even a “small” false-positive rate creates real collateral damage at scale.

| False-positive rate | Expected false accusations (out of 200) | Practical impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | ~2 | A few stressful conversations; still non-trivial harm risk. |

| 5% | ~10 | Now you’re running a mini-tribunal every week—trust erodes fast. |

Illustrative math, not a guarantee—real rates vary by tool, text type, and thresholds.

The metric trap: overall accuracy can look great while outcomes are still unfair

UPenn’s Chris Callison-Burch put it plainly: “These claims of accuracy are not particularly relevant by themselves,” because you can “improve” detection by flagging more human writing too (EdScoop). In other words: overall accuracy can hide the exact failure mode you care about—false accusations—especially when the base rate of human writing is high.

Once you accept that, the next question is practical: where do detectors break first?

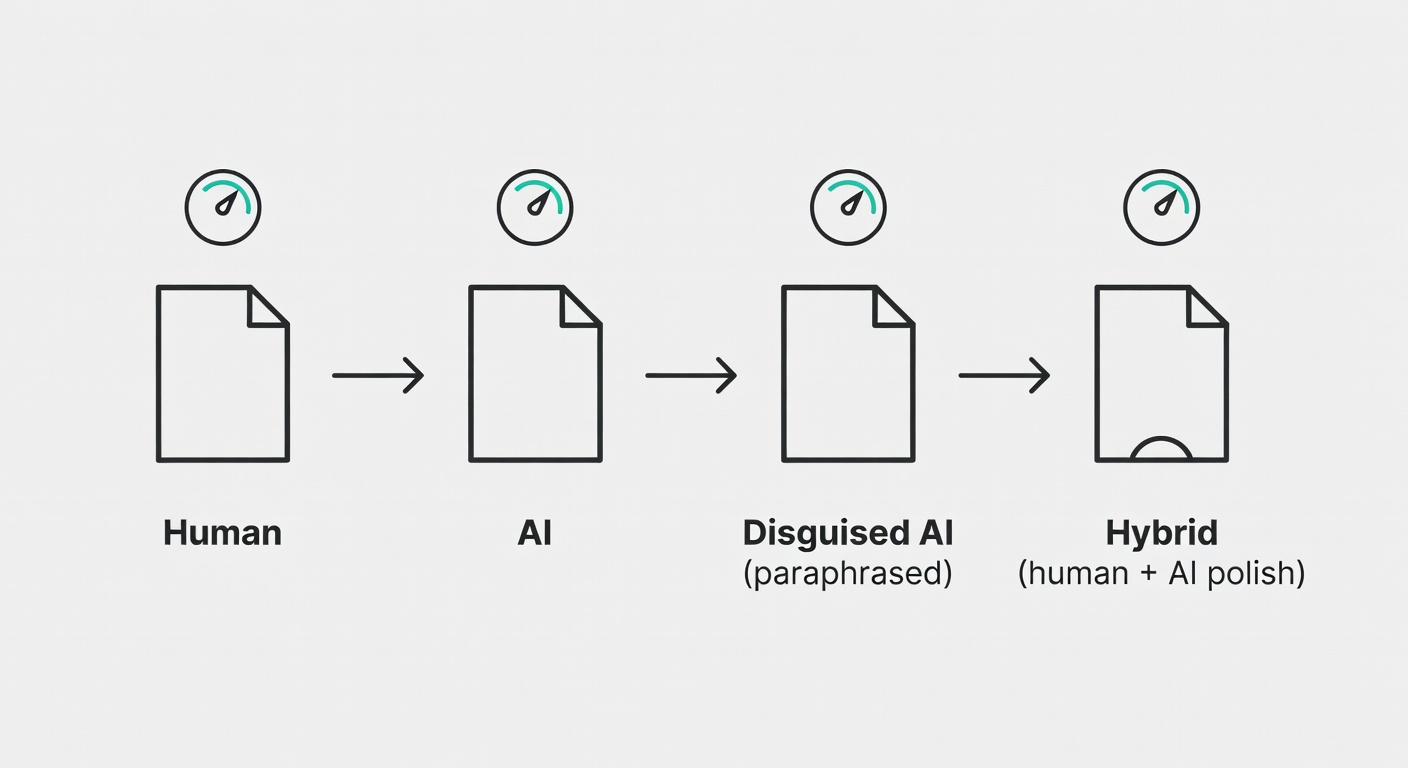

Where Detectors Fail in the Real World: Hybrid Text, Paraphrasing, and “AI-but-not-really” Writing

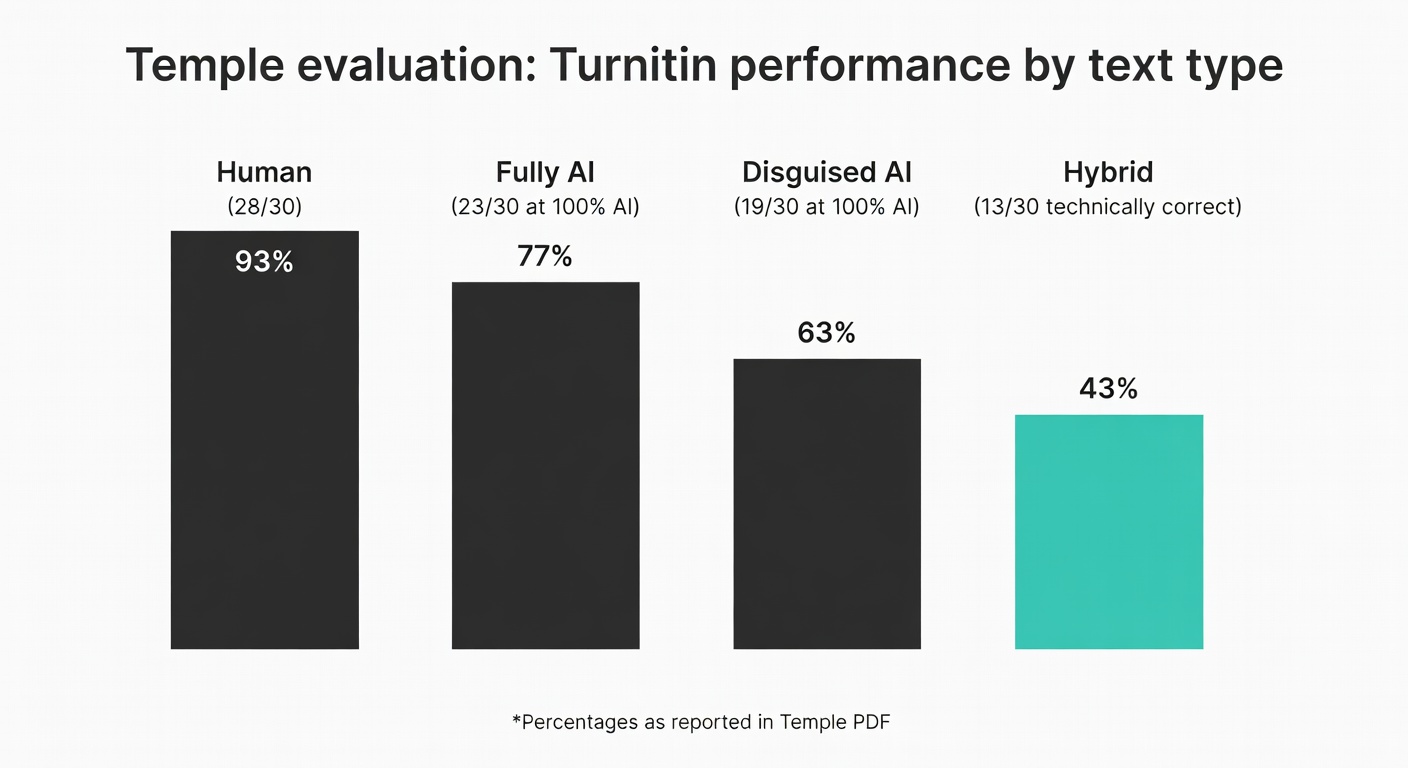

Temple tested Turnitin on 120 samples: 30 human, 30 AI, 30 “disguised” AI (paraphrased), 30 hybrid (Temple PDF):

- Human texts correctly identified 28/30 (93%)

- Fully AI texts identified as 100% AI in 23/30 (77%)

- Disguised AI identified as 100% AI in 19/30 (63%)

- Hybrid texts “technically correct” (neither 0% nor 100%) only 13/30 (43%) (Temple PDF)

If hybrid writing is allowed (or even tolerated), the operational move is to stop pretending a percentage equals authorship. Require disclosure and process notes up front—MIT’s “process statement” idea is a clean way to normalize that without turning every submission into an interrogation (MIT Sloan).

Reality Check Grid: What Breaks Where

| Human | Fully AI | Disguised AI | Hybrid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What detectors handle well | Consistent personal style; longer prose (KU CTE) | Unedited model output; “clean” AI patterns (Temple PDF) | Sometimes catches it, but recall drops as edits increase (Temple PDF) | Mostly struggles; attribution gets noisy (Temple PDF) |

| Common failure mode | False positives on formulaic/technical prose (USD) | Misses when output is lightly rewritten or mixed with human text (KU CTE) | Paraphrase/humanizer edits evade pattern-based detection (USD) | Sentence-level flags don’t map to “who wrote what” (Temple PDF) |

Why sentence-level “flagging” is especially shaky

Plagiarism tools can show receipts (matched text + a source); AI detectors mostly provide inference without link-backs. Temple’s evaluation found that in hybrid samples, flagged sentences didn’t reliably correspond to the AI-generated portions (Temple PDF). Treat highlights as “areas to review,” not forensic evidence.

Tool-by-Tool Reality Check: Turnitin vs GPTZero vs Others (How to Read the Claims)

Vendor benchmarks are data points, not verdicts. A practical evaluation framework is boring—but it works:

- What was tested? Hybrid, paraphrased, domain-specific, short answers vs long-form prose.

- What thresholds? “Accuracy” changes dramatically with operating point (false positives vs false negatives).

- How often does it update? Detectors can lag behind new models and new evasion tricks (EdScoop).

- What’s the stated error tradeoff? Some tools explicitly bias toward fewer false positives (Turnitin).

One caution: these numbers aren’t directly comparable across tools without shared datasets and shared thresholds.

For Turnitin specifically, KU’s CTE notes it reports scores with 98% confidence, but appears to have a ±15 percentage point margin of error—so “50%” could plausibly be “35–65” (KU CTE). That’s not useless; it’s just not courtroom-grade.

GPTZero publishes big numbers too: in a 3,000-sample benchmark it reports 99.3% overall accuracy and 0.24% false positives (vendor-reported) (GPTZero benchmark). In a separate post, it claims strong results on the independent RAID benchmark, including detecting 95.7% of AI texts while misclassifying 1% of human texts as AI (GPTZero RAID claim). Those are interesting signals—but you still need to ask whether the benchmark resembles your actual submissions.

| Claim | What to ask | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Overall accuracy | What’s the base rate of AI in the test set? What’s the threshold? | Can look great while still producing harmful false positives (EdScoop). |

| False-positive rate | Measured on what kinds of human writing (technical? ESL? short?) | False accusations are the highest-trust risk (MIT Sloan). |

| False negatives / recall | How much AI does it miss when text is edited or hybrid? | Low FP often implies more misses (USD). |

| Confidence / margin of error | Is there an uncertainty band (e.g., ± points) and how should it be interpreted? | Prevents over-reading a single number (KU CTE). |

| Dataset type | Does it include hybrid and paraphrased samples? | Hybrid is the common failure mode (Temple PDF). |

| Update frequency | How often is the detector retrained or recalibrated? | Detectors can lag behind new models and evasion tricks (EdScoop). |

Evasion, Adversarial Attacks, and the Arms Race Problem

If someone is motivated to bypass detection, detectors are a weak gate. EdScoop describes UPenn research showing simple “adversarial attacks” can break detectors: whitespace tricks, misspellings, selective paraphrasing, and homoglyphs (characters that look identical to humans but differ to computers). Callison-Burch says homoglyph attacks can drop performance by ~30% (EdScoop).

USD’s guide also notes common circumvention methods like paraphrasing and “humanizer” services (USD). If your policy assumes “detector = enforcement,” you’re effectively outsourcing judgment to a system that’s easy to game and hard to audit.

Bias, Equity, and Collateral Damage: Who Gets Hurt by False Positives

USD summarizes studies suggesting non-native English writers and neurodivergent students may be flagged at higher rates, due to reliance on repeated phrases and simpler structures (USD). KU’s CTE echoes that research caution exists and explicitly warns against evaluative use for non-native speakers—though it notes Turnitin wasn’t part of that particular study (KU CTE).

Mixed evidence doesn’t mean “ignore it.” It means your process has to be robust under uncertainty: don’t escalate to punishment based on a score alone, and make sure students have a fair way to respond (MIT Sloan).

A Practical, Low-Drama Workflow: How to Use Detector Output Without Making It the Verdict

- Check assignment fit. Does the detector even claim to work on this format (long-form prose, enough words)? KU notes Turnitin doesn’t work well on short text, lists, or bullet points (KU CTE).

- Compare against prior writing. Style shifts are often more informative than a raw score (KU CTE).

- Request process evidence. Drafts, notes, outlines, version history—MIT recommends process statements to normalize disclosure (MIT Sloan).

- Have a conversation. KU’s guidance: talk with students, ask them to explain choices and concepts (KU CTE).

- Offer a redo when appropriate. KU explicitly suggests a second chance if doubts remain (KU CTE).

- Document decisions. Not because you’re building a case—because consistency matters.

Concrete example: a student gets flagged at 60%. They open Google Docs and show version history with timestamps, incremental edits, and early messy drafts. That’s often more persuasive than any detector score. (And if the history shows a single paste of a polished essay, that’s also useful context.)

What counts as “better evidence” than a detector score

MIT’s recommendation of a process statement is a solid baseline: ask students to explain how they completed the work and whether/how they used AI (MIT Sloan). KU’s CTE pushes similar “human” checks: compare style, then talk with the student (KU CTE).

- Version history (Google Docs / Word) and drafts

- Outlines, research notes, annotated sources

- Oral walkthrough: “Explain this paragraph and why you cited X”

- Where available, authorship verification tooling (supporting context, not magic)

If your policy punishes honest disclosure, you’ll train students to hide their process—exactly the opposite of what you want.

Conclusion: Use Detectors as Smoke Alarms, Not Verdicts

Detector scores are best treated as smoke alarms: they tell you where to look, not what happened. If you’re an educator or editor, the practical call to action is straightforward: publish a clear AI-use policy, require process evidence (drafts/version history/process statements), and document a consistent human review path before you ever escalate a case (MIT Sloan; KU CTE).

The line I keep coming back to is simple: if the tool can’t show receipts, it can’t be the judge.

Numbers to keep in your head

- <1% document-level false positives is Turnitin’s stated goal (for documents with ≥20% AI writing) (source).

- ±15 percentage points is the margin of error KU CTE suggests for interpreting Turnitin scores (source).

- 13/30 (43%) is Temple’s “technically correct” rate for hybrid texts in their Turnitin evaluation (source).

Sources

- MIT Sloan Teaching & Learning Technologies: “AI Detectors Don’t Work. Here’s What to Do Instead.”

- University of San Diego Law Library Guide: “The Problems with AI Detectors: False Positives and False Negatives”

- University of Kansas CTE: “Careful use of AI detectors”

- Temple University evaluation (PDF): “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Turnitin’s AI Writing Indicator Model”

- Turnitin blog: “Understanding false positives within our AI writing detection capabilities”

- Turnitin blog: “Understanding the false positive rate for sentences of our AI writing detection capability”

- EdScoop: “AI detectors are easily fooled, researchers find”